Research in our laboratory focuses on understanding the interactions between plants and herbivores.

Illustration by Nick Sloff

Much of our study has been on induced defenses in plants against insects. Our model system of study often includes the tomato plant Solanum lycopersicum and the tomato fruitworm Helicoverpa zea (aka corn earworm, cotton bollworm). Our latest research is centered on two main questions:

How do plants recognize insect herbivores?

When herbivores initiate feeding on a host plant, they present "cues" that the plant perceives and uses to rapidly mobilize induced defenses in response to the attack. Besides the mechanical damage cues that accompany feeding, plants perceive and integrate an array of herbivore cues-- originating with the initial contact of the herbivore on the plant, followed by feeding cues that include the secretion of saliva, and culminating with the excretion of their wastes.

H. zea larva on a tomato leaf. Photo by Nick Sloff

(Link: Video of H.zea eating a tomato leaf. Video by Michelle Peiffer)

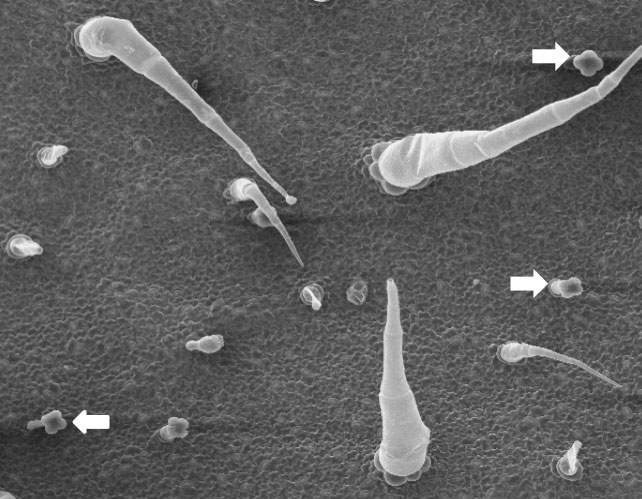

Trichome Project: Plant trichomes play important roles in defense against herbivores by serving as physical and chemical defenses. In addition, we have found that the glandular trichomes of tomato contain defense signaling molecules and when they are disrupted by herbivore movement cause the upregulation of plant defenses. These results suggest that glandular trichomes can act as sensors that detect activity on the leaf surface, and ready plants for attack by herbivores. This project is supported by a USDA NRI proposal.

Scanning electron micrograph of trichomes on the surface of the tomato leaf. White arrow indicates the type VI trichome which releases a sticky substance when disrupted. Photo by Donglan Tian

Female O. insidiosus on the underside of a tomato leaf. The predator's feet are entangled in the sticky exudate of type VI glandular trichomes, which density was artificially increased by a spray of methyljasmonate. Photo by Helene Quaghebeur

Saliva Project: Plants rely on rapid and accurate recognition of herbivore feeding cues to mobilize induced defenses. Yet relatively little is known about the molecular recognition events that occur at the plant-herbivore interface. Our project focuses on the salivary proteins from Helicoverpa zea that are potent elicitors of defenses in tomato fruit and in foliage. Our specific objectives are to: 1/ characterize salivary components involved in elicitation of induced defenses in tomato; 2/ characterize plasticity in salivary gene expression; and 3/ conduct functional analyses of selected salivary genes. This project is supported by a USDA AFRI project.

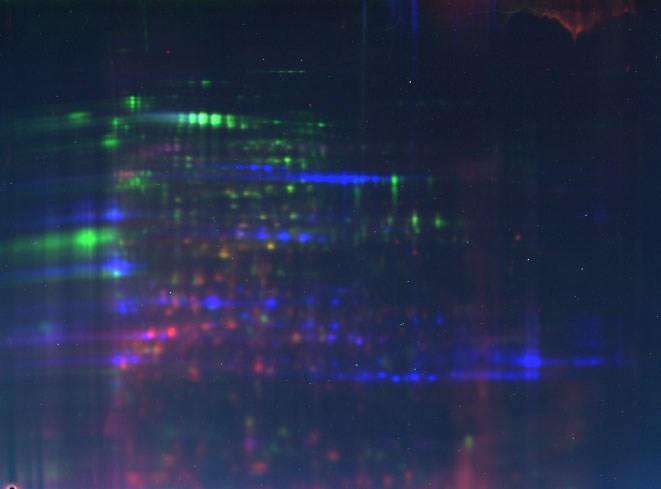

2-dimensional electrophoresis gel of 3 secretions from H. zea. Each secretion is stained with a different fluorescent dye then electrophoresed together to compare proteins between samples. Green spots represent secretions from H. zea saliva; red spots are regurgitant; and blue spots are secretions from the caterpillars' ventral eversible gland. Yellow spots indicate proteins present in both saliva and regurgitant. Photo by Frederic Francis of Gembloux University, Belgium.

How do herbivores evade detection?

Do some herbivores avoid "presenting cues"? Alternatively, do some herbivores deliver effectors that enable their evasion of host plant defenses? This project involves two model plant systems: tomato and maize. We are comparing the ability of specialist and generalist herbivores in their ability to evade host defenses. We are studying how herbivores evade detection by either minimizing the display of their cues and/or by the secretion of effectors that help suppress defenses. The project has been supported by NSF and is now supported by a new grant from USDA AFRI.

H. zea moth laying eggs on a tomato plant. Photo by Jinwon Kim

Colorado potato beetle larva feeding on tomato leaves. Photo by Nick Sloff

Research Opportunities

During the summer of 2013, our laboratory hosted two undergraduate students from the University of West Alabama. Morgan Elston and Brittany Harry competed research projects and presented their findings at the Undergraduate Research Symposium in Hershey Pa in August 2013.

Outreach

Research in our laboratory focuses on how insects may use bacteria to avoid detection by the host plant. Seungho Chung, currently a post-doc in the lab, has discovered that the Colorado potato beetle regurgitates bacteria onto tomato plants while feeding. His work was recently published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and shows that these bacteria suppress the plants' defenses against the beetle and allow the beetles to grow better. To help the public understand this complex concept, at the recent Great Insect Fair, held October 5, 2013 at the Bryce Jordan Center, our laboratory hosted "Beetle Bowling". An educational display included live beetles, scanning electron microscope images of the bacteria, and fluorescent microscope images of "beetle barf". Kids of all ages donned beetle antennae and rolled "bacteria" down a bowling lane to knock down the plant defenses.

Kids participate in "Beetle Bowling" (left) while visitors fill the arena floor during the October 2013 Great Insect Fair (right).

Staffed by lab members and local high school students, fulfilling a community service requirement, our booth had about 800 kids participate. Many parents, recognizing the beetles from their home gardens, chatted and asked us questions while the kids enjoyed bowling. By the end of the day many people had a better understanding of plant insect interactions.

Lab Members

Graduate Students

-

Flor Edith Acevedo

-

Loren Rivera-Vega

-

Ching Wen Tan

Postdoctoral Scholars

-

Seung Ho Chung

Research Support Assistant

-

Michelle Peiffer

Graduates

-

Seung Ho Chung, December 2013, currently a postdoc in our lab

-

Donglan Tian, PhD August 2012, currently a Research Scientist at Bayer Crop Science, Davis, CA

-

Jinwon Kim, PhD December 2012, currently a Postdoctoral Scholar at Université de Neuchâtel, Switzerland