Posted: April 8, 2021

IBC Fellow and Entomology graduate student Codey Mathis interviews Dr. Michael Skvarla on new publication about periodical cicadas

Photo by Tracy Lee, Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

“Cicadapocalypse!” “Brood X is coming!” If you live in the eastern United States, you’ve likely heard that this year is going to be “the big one” for cicadas. But what exactly does that mean? How are these “periodical” cicadas different than our annual cicadas, and should we be concerned? I interviewed Dr. Skvarla, Assistant Research Professor of Arthropod Identification in the Entomology Department at Penn State and author of a revised Penn State Extension fact sheet on periodical cicadas, to get the basics. Interested readers are encouraged to check out the factsheet.

We are used to cicadas being the soundtracks of our summers. Annual cicada species emerge every year starting in July, males singing their buzzy songs to entice females to mate and continue throughout September. Periodical cicadas, though, emerge every 13- or 17 years in late May and live only for a few weeks. “The reason that periodical cicadas emerge en masse the way they do is predator avoidance,” explains Dr. Skvarla. “If you’re one in a million, you have a much lower chance of getting eaten than if you’re one in a dozen or one in a hundred.” Because of this, periodical cicadas often emerge all at once – seemingly overnight, areas with a periodical cicada brood will be covered in screaming cicadas. “They all come out simultaneously to avoid getting eaten. Stragglers get picked off.” This strategy is very different than that of our annual cicada species. “They emerge every year and have smaller population sizes, so they have a different life history. They avoid predators by hiding in trees.” It is easy to tell the difference between annual and periodical cicadas, not just by the time of their emergence, but also their color (see picture below). The green of the annual cicada makes them difficult to see while singing amidst the treetops.

Image by Matt Bertone, used with permission.

But just how many periodical cicadas can we expect to see? “In areas that have heavy periodical cicada emergence”, answers Dr. Skvarla, “you can expect tens of thousands to millions emerging, and billions throughout the entire range. In some places, they can be dense enough that the noise is a cacophony of sound. Not quite deafening, but very loud: you won’t need ear protection, but you can’t hold a conversation. The densest populations will be in rural areas and woodland settings. In places of high agricultural use and urban settings you can expect to see fewer.”

Cicadas live as nymphs underground, tapping into tree roots to suck up their sap. When the soil temperature is right (64°F), they emerge from belowground and climb up nearby tree trunks, molting into their adult form and leaving behind their shed exoskeleton. At this point, the males begin to sing to attract mates, and the females pick a mate. The females then lay eggs in twigs and branches of woody vegetation, some laying up to 600 eggs! When the eggs emerge a few weeks later, they drop to the ground and burrow underneath, beginning their 17 years of feeding on tree roots.

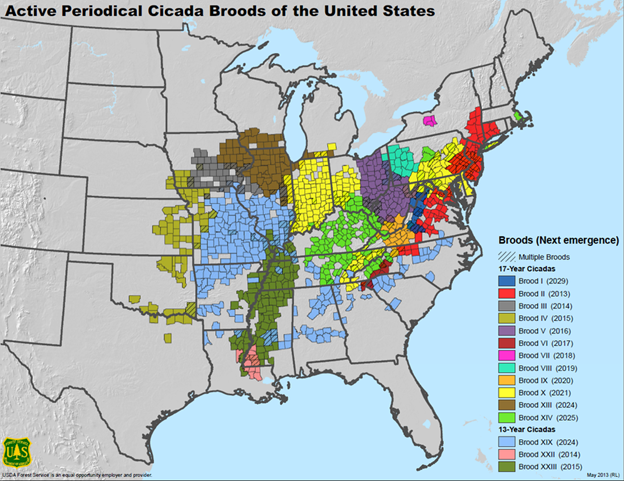

Image by A. M. Liebhold, M. J. Bohne, and R. L. Lilja, USDA Forest Service. (2013). Public Domain.

Across the Northeastern United States, there are multiple generations (“broods”) of periodical cicadas, and this year it’s Brood X’s turn. This brood (pronounced “brood ten”), is set to emerge in southern Pennsylvania, western Ohio, Illinois, and eastern Tennessee (see map below). Centre County, where Penn State is, won’t see periodical cicadas this year, although Brood XIV is expected to emerge emergence in 2025. While adult cicadas do not bite or sting, and therefore do not pose a threat to humans or their pets, they damage trees during the egg laying process, which can be fatal to small, stressed trees. Big, healthy trees aren’t at much of a risk.

While to some, the noise may be a nuisance, to say that local entomologists are excited would be an understatement. “It’s one of the grand phenomena of nature,” remarks Dr. Skvarla. “I’ve never experienced a periodical cicada emergence, so this year we’re planning the 2-hour drive to go visit them. I want to experience it.” I, like Dr. Skvarla, am eagerly looking forward to their emergence. As someone from the Pacific Northwest, annual cicadas were already a novelty, but the ephemeral periodical cicada emergence will be another item off my personal bucket list.

Still curious about cicadas? More information, including ways to mitigate possible damage from periodical cicadas, can be found at the Penn State Extension Factsheet about periodical cicadas, written by Dr. Skvarla. A Spanish translation of the factsheet can be found here. For more neat insect images, see Dr. Matt Bertone’s Flickr Page.

Contact Information